Our Native Marañón (Cashew)

Woo-hoo! After talking about the Mimbro, Manzana de Agua and Snake Fingers we have finally found a fruit that is native to our area – the Cashew, or Marañón as it is locally known. But is it a fruit or a nut? Both? Yes! Many newcomers recognize the cashew nut but know little about the fruit itself. The cashew offers far more than just a tasty snack. Its husk and toxic shell serve important roles in industrial applications. The tree’s timber, leaves, and bark also provide value across many uses. This plant stands out as both versatile and impressive.

THE FRUIT & NUT

Not a True Fruit!

The Cashew Apple is a sweet, juicy, and slightly tangy fruit. Some people boil it in salt water to mellow the flavor, though that step isn’t required. Below the apple sits a single nut—just one per fruit. Interestingly, the Cashew Apple isn’t a true fruit. It’s an accessory fruit, while the actual fruit is the kidney-shaped drupe that encases the cashew nut. This unique structure makes the cashew one of the most unusual and fascinating plants in tropical agriculture.

WATCH THE TOXICITY!

Marañón allergies affect a significant number of people—around 6% of children and 3% of adults. Cooking doesn’t eliminate the risk, since the allergy-triggering proteins remain stable at high temperatures. The shell of the cashew, usually removed before sale, poses another hazard. It contains compounds that can cause severe skin reactions, similar to poison ivy. These reactions often result in painful dermatitis, especially if the shell oil comes into contact with bare skin. Handling raw cashews requires caution and proper processing.

SO MANY USES!

Nut:

Cashew nuts serve many roles in cooking, much like other tree nuts. People enjoy them as snacks or add them to meals and salads for extra texture and flavor. In South Asian cuisine, cooks often grind cashews into a paste to create rich bases for curries and sweets like kaju barfi or butter chicken. Cashew shavings also make popular toppings for desserts, adding a creamy crunch. Beyond the nut, cashew sprouts are edible too—eaten raw or cooked, on their own, in salads, or as garnishes. This versatility makes the cashew a true culinary gem.

Apple:

The Cashew Apple offers a burst of sweet, tangy flavor and plenty of culinary flexibility. You can eat it fresh, simmer it into curries and sauces, or ferment it into vinegar and citric acid. Like other tropical fruits, it works beautifully in preserves, chutneys, jams, sweets, and juices. Its bold taste pairs especially well with alcoholic drinks, making it a popular mixer in cocktails. In Panama, cooks boil the fruit with water and sugar to create a rich, syrupy dessert. It’s a versatile ingredient with deep cultural roots—and yes, there’s still more to explore!

Goa Alcohol

In Goa, one of the earliest regions to receive cashew trees from Portuguese explorers, locals developed a unique tradition around the fruit. They collect ripe cashew apples, mash them, and extract a sweet juice known as neero. After fermentation, this juice becomes the base for two distinct spirits. The first distillation produces urrak, a light and fruity drink with around 15% alcohol. A second distillation transforms it into fenny, a stronger, aromatic spirit that reaches about 40–45% alcohol. Both drinks hold deep cultural significance and reflect Goa’s rich history of innovation and celebration.

Other Drinks

In Tanzania, locals dry the Cashew Apple, rehydrate it with water, and ferment it to produce a potent liquor known as gongo. This drink holds a strong place in rural traditions, often made in small batches and shared within communities. Across Asia and Africa, many cultures have developed their own methods and names for cashew-based spirits. From fenny in Goa to regional brews in West Africa and Southeast Asia, the Cashew Apple continues to inspire a wide range of local liquors—each with its own flavor, strength, and story.

Nut Oil

Cashew Nut Oil adds a rich, nutty flavor to cooking and works beautifully as a salad dressing. Producers typically use nuts that are cracked, misshapen, or unsuitable for direct culinary use. These nuts still contain valuable oils and nutrients. The highest quality oil comes from a single cold-pressing process, which preserves flavor, aroma, and nutritional content. Cold-pressed cashew oil is prized for its smooth texture and subtle taste, making it ideal for sautéing, drizzling, or blending into sauces and dips.

Shell Oil

Cashew Shell Oil, also called Cashew Nut Shell Liquid, is a natural resin produced during nut processing. It differs from edible cashew nut oil and contains strong irritants that require careful handling. The shell oil makes up about 15–30% of the shell’s mass and offers a wide range of uses. It plays a role in folk medicine, timber treatment, and wastewater absorption. Industries also use it to create bio-based monomers, carbon composite resins, and materials for electrical energy storage. This by-product turns waste into value and highlights the cashew’s industrial potential.

Timber

Cashew timber serves many practical uses across tropical regions. Builders use it in boat construction, packing crates, and furniture making due to its workable density and durability. Locals also shape it into house-boards and handcrafted items. When cooked, the wood produces high-quality charcoal, valued for its heat and burn time.

Husk

The cashew husk makes up less than 5% of the nut and forms the thin, dry outer layer that wraps around it. Though not edible, it holds surprising industrial value. Researchers and manufacturers use it as an adsorbent in filtration systems and wastewater treatment. It also plays a role in creating composites, biopolymers, and natural dyes. In enzyme synthesis, the husk contributes as a bio-based material with reactive properties.

Bark

Cashew bark produces a yellow resin known as Cashew Gum. This natural gum works well in adhesives thanks to its sticky, water-soluble properties. Industries also use it in coatings, emulsifiers, and stabilizers. Researchers have explored its role in biomaterials, where it supports gels, films, and other engineered compounds.

Leftovers

Cashew plant waste offers surprising value beyond the nut. Farmers use discarded husks, broken nuts, and leftover pulp as animal feed, especially for chickens, ducks, and pigs. The leaves also provide nutrition and bulk in mixed feed. In many regions, people burn cashew waste as biofuel—using it for heat or to power kitchen stoves. Every part of the tree, from roots to bark, can be composted or processed into organic fertilizer.

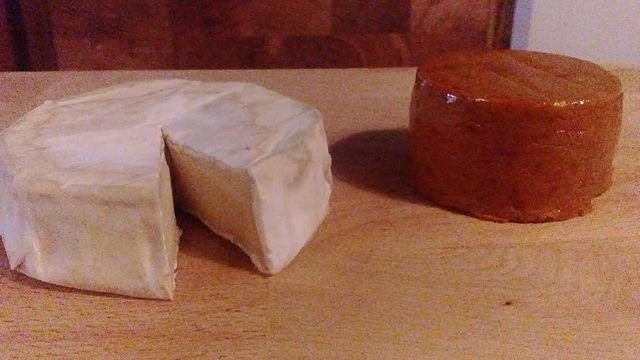

FAKE MILK, CHEESE AND BUTTER

Cashews offer a plant-based alternative to many animal-derived foods, with cashew milk standing out as a popular choice. Known for its creamy texture, cashew milk often feels richer than almond milk and contains more protein and fat. It’s especially high in iron and magnesium, nutrients that support energy levels and bone health—making it a strong option for women and those with specific dietary needs.

Cashew milk also has a lighter environmental footprint. While almond milk requires large amounts of water—up to a gallon per almond—cashew trees rely mostly on rainwater, reducing strain on aquifers. This makes cashew milk a more sustainable choice in regions facing water scarcity.

Cashew Cheese is a popular vegan food, as is Cashew Butter.

THE GIANT CASHEW TREE

No article on cashews feels complete without honoring the legendary Cashew of Pirangi. This colossal tree sprawls across more than 2 acres—an entire city block in Pirangi do Norte, Brazil. Each year, it produces over 60,000 cashew fruits, averaging more than 160 per day. Its growth pattern is as extraordinary as its size. The tree expanded outward by dropping heavy branches that rooted themselves, forming a tangled network of trunks and limbs that now resemble a forest more than a single tree.

Though some claim it was planted in 1888, one study suggests the tree may be over 1,000 years old. Today, roads and buildings contain its spread, but its legacy continues to grow.

THE MORE BORING CASHEW TREES

Cashew trees usually grow up to 14 meters or 45 feet tall, but commercial growers often prefer dwarf varieties that reach only about 6 meters or 20 feet. These smaller cultivars mature faster and produce up to four times more fruit and nuts per acre. Cashews thrive in tropical climates between 25° north and south of the equator. They prefer well-drained sandy or loamy soils and need plenty of sun. Once established, the trees handle dry periods well, making them a resilient crop in regions with seasonal drought.

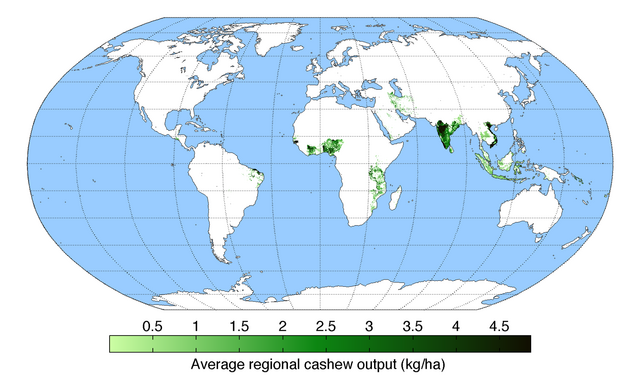

DISTRIBUTION & CULTIVATION

The Cashew tree originated in the tropical regions of South America, with Brazil as its ancestral home. Portuguese explorers began spreading the tree globally in the 1500s, recognizing its value early on. By the 1550s, Brazil had started exporting cashew nuts. Between 1560 and 1565, the tree reached Goa in India, where it quickly took root. From there, it spread across Southeast Asia and eventually into Africa.

Today, cashew cultivation thrives in tropical zones around the world. Côte d’Ivoire leads global production, followed closely by India and Vietnam. Other major producers include the Philippines, Tanzania, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Our tropical area boasts untold variety of strange, exotic, and tasty produce – a visit to a local fruit stall will leave you speechless! Imagine living in a beautiful, tropical land where each day brings an explosion of new tastes and wonder – you can make this dream a reality much quicker than you think! Take the first step by browsing our local property listings here. RE/MAX WE SELL PARADISE is your trusted partner in this land of exotic and tropical culinary delights – we are waiting for your call!

Cover photo c/0 Vinayaraj, wikicommons.