Oxcarts – A National Symbol of Costa Rica

The Costa Rican Oxcart, or Carreta, rose from its humble beginnings, in the early 1800s to become one of the most striking and recognizable symbols of the country. In 2005 it was granted the coveted ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage‘ status by UNESCO. Every bit of Costa Rican heritage is woven into the Oxcart – the country’s topography, agriculture, demographics, roads, weather, commerce, and art & cultural expression have all left their mark on the revered Carreta – a vehicle which has evolved to create a cozy niche within the landscape of Costa Rica.

🐂 THE OXCART IS STILL THRIVING

And while modern technology in the form of tractors, pick-up trucks, large transport vehicles and trains has largely replaced the role of the Oxcart, there is still a place for it in our society. And this place exists in the thriving cultural heritage scene of the country such as parades, religious celebrations, traditional functions, artesian shows, and festivals as well as in very practical areas as the Oxcart is still used where modern vehicles fail to deliver (or where farmers take pride and pleasure in using the Oxcart for various tasks as a symbol of their past)- and so the Carreta can truly be considered a living and thriving element of the Costa Rican heritage.

🤠 THE OXCART’S HUMBLE BEGINNING – AND THE BIRTH OF THE BOYEROS

The Oxcart accompanied the Spanish settlers upon their arrival in Costa Rica, back in the 1500s when it was a very simple design made of undecorated lumber. Initially the carts were used for transportation to and from work as they would have been used in Spain. Other tasks included turning the mill wheel, plowing the fields, transporting sick people to medical help, delivering firewood, and all kinds of general transportation tasks.

You’re not in Kansas anymore!

However, the climate of Costa Rica is vastly different from the Iberian lands thousands of miles away. And so the Oxcarts did not perform as intended – the local mud, sand, swamps & rivers, unprepared roads, and thick vegetation played havoc with the vehicle which often got stuck or suffered from wheel damage – and this was exacerbated by the emerging long-distance transportation links that developed along the developing coffee and agricultural produce trade routes. So, starting in the mid-1800s, the settlers developed a new design for the wheels – they ditched the spokes and crafted an ingenuous disc-like innovation, said to be based on the wheels used on children’ toys by the Aztec people. This proved to be a winning and effective update which marked the birth of the Costa Rican Oxcart as we know it.

Welcome Boyeros!

Costa Rican Oxcart drivers acquired the name Boyeros, and their tasks also includes breeding the oxen, caring for the animals, and training the Ox to pull the Oxcart. The Boyeros were, and are, highly skilled and highly respected – as the livelihood of families and, in the years past, entire communities depends on their skill, strength and expertise.

NOW TIME FOR SOME COLOR AND FLAIR

Beyond the signature closed-wheel structure, Costa Rican Oxcarts stand out for their dazzling, hand-painted designs that turn each cart and harness into a moving canvas. These vibrant patterns—swirling, geometric, floral—are never repeated, making every cart a singular expression of artistry and pride.

This wasn’t always the case. In their earliest form, Oxcarts served a strictly functional role. Built from unadorned wood and fitted with basic leather coverings, they were either left bare or coated in tar for durability. Over time, necessity gave way to creativity, and utility evolved into cultural expression. Today, the transformation from plain transport to folk masterpiece reflects not just aesthetic flair, but a deeper celebration of identity and craftsmanship.

The custom of painting Oxcarts began in the early 1900s in Sarchí, sparked by the creativity of Joaquin Chaverri at his local workshop. Chaverri, a craftsman and factory owner, used his cart not just for work but for leisurely Sunday outings with his family. Wanting those rides to reflect pride and elegance, he began adorning the cart with decorative patterns.

At first, orange dominated the palette—simply because it was the only paint available in town. As the practice spread, other colors joined the mix, but orange remained the signature hue of Costa Rican Oxcarts and their equally ornate bull harnesses. Over time, these painted carts came to represent more than transport. Their vivid designs signaled craftsmanship, prosperity, and social standing. The more elaborate the decoration, the greater the prestige of the household behind it.

EACH OXCART HAS A UNIQUE SONG

A series of metal rings attached to the wheel produce a very unique sounds – each Oxcart has its own ‘song’ as it moves along its tasks. The sound was a source of pride and complimented the colorful designs of the Oxcart. It was also useful in alerting residents of who is passing their home or heading in their direction – as the unique sounds of individual Oxcarts became a sort of ‘calling card’ across the landscape, being associated with specific people and families.

THE COFFEE TRADE

Oxcarts began as practical tools, ferrying laborers to their jobs and assisting with daily agricultural tasks across rural Costa Rica. By the mid-1800s, however, the booming coffee industry demanded more—beans grown in the Central Valley had to reach shipping hubs on both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, a grueling trip that could stretch from ten to twenty days.

This arduous trek reshaped the Oxcart itself. The strain of the journey and the heavy coffee loads spurred innovations in wheel design and overall structure, transforming the cart into a cornerstone of Costa Rican progress. Builders responded by crafting lighter, sturdier carts that could better handle the demands of loading, hauling, and unloading coffee. Though coffee earned fame as the cart’s iconic cargo, it shared space with other staples—corn, sugar cane, bananas, and more—all bound for the ports of Puntarenas and Limón. On the return, carts rarely traveled empty, often bringing salt and other traded goods back to the valley’s communities.

THE TRADITION LIVES ON

Painted oxcarts remain a vivid part of Costa Rican life, especially during festivals and religious celebrations where tradition takes center stage. Their bold designs and intricate patterns reflect generations of craftsmanship and cultural pride. Beyond ceremony, oxcarts still serve practical roles. In rural areas and agricultural zones, modern versions haul goods and supplies with steady reliability. If you’ve driven past the palm oil plantations between Jacó and Quepos, you’ve likely seen them in action—rolling through the fields or driving along the Costanera, pulled by tractors instead of the hardy Oxen.

El Día del Boyero

…or National Boyero Day, is celebrated on the second Sunday of March. This holiday primarily honors the Boyeros and the Costa Rican Oxcart tradition. The heart of the celebration takes place in the city of Escazu where traditional dancers, performers, and craftsmen share their passion for their past, present and future. Fairs, cultural events, and traditional food and craft stalls burst to life after the rains, revealing Costa Rica’s vibrant heritage. The highlight, though, is the dazzling Oxcart parade—an explosion of color where carts and oxen wear their finest for the occasion.

After the parade, Boyeros in traditional dress receive honors from local dignitaries, cheered on by festive crowds. Escazú hosts the main celebration, but smaller, equally spirited events unfold in towns and villages across the country.

Each gathering reflects deep pride, community spirit, and the enduring legacy of Costa Rican tradition.

WHAT IS AN ‘OX’ ANYWAYS?

An ox is simply a castrated bull—this calms the animal and removes the aggression typical of intact males. In contrast, a bull remains uncastrated, while a cow refers to a female. Another common name for an ox is “bullock,” especially in British English. Humans began domesticating oxen over 6,000 years ago, using them for plowing, hauling, and other heavy tasks. Their strength and steady temperament made them ideal partners in early agriculture and transport.

COMMEMORATIONS OF BOYEROS AND FARMERS

Costa Rica takes deep pride in its farmers, Boyeros, and the iconic oxcart—a symbol woven into the nation’s identity. Across the tropical landscape, monuments and tributes honor this heritage, celebrating the strength and tradition of rural life.

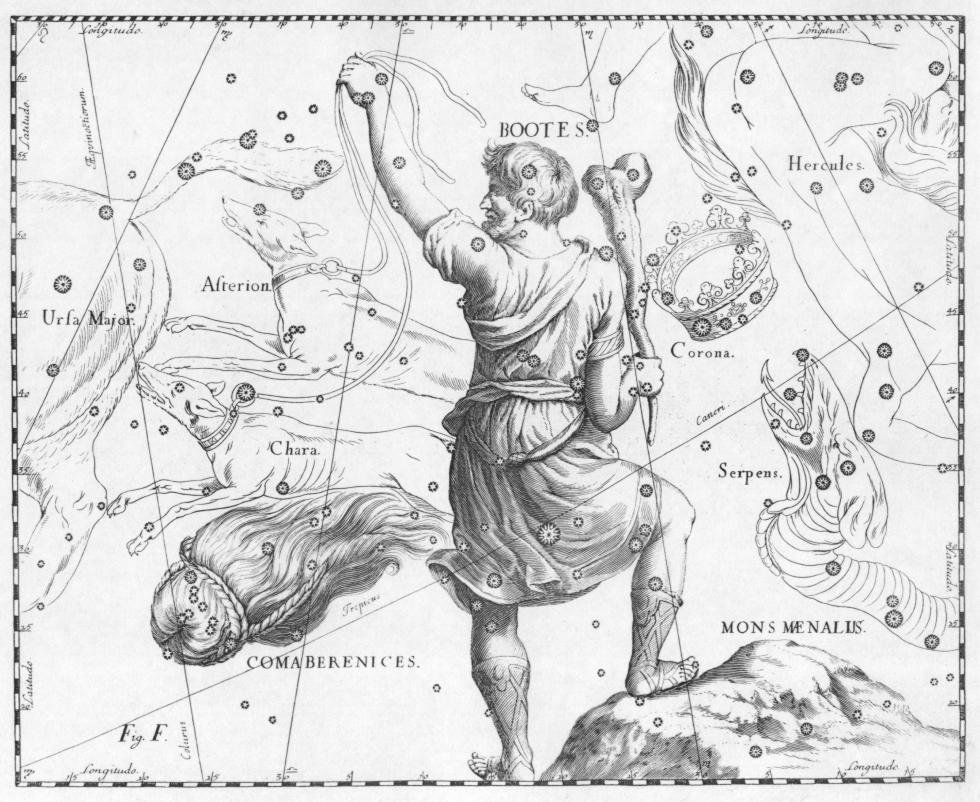

Beyond the earthbound legacy, the Boyero even reaches the stars. An ancient constellation bears his name, depicting a shepherd gazing toward the Big Dipper. This celestial nod reflects the timeless respect for those who guide, labor, and watch over the land.

Costa Rica boasts a deep, engaging and proud culture – from its pre-Colombian roots to current customs that evolved over the past hundreds of years the traditions, music, dance, feasts and festivals are as colorful as the country’s wildlife! RE/MAX WE SELL PARADISE can help you relocate to this amazing country and as you browse our current listings – here – imagine life in such a vibrant and amazing location!