Our Troublesome Pizotes

What is this animal that gets in our garbage, eats our banana crops and starts fights with our dogs? They are sneaky and they are everywhere – found all over Costa Rica the White-Nosed Coati, or our troublesome Pizotes, are both loved and hated, a true jack-of-all-trades that will eat anything and is as comfortable in the densest mountain jungles as it is in the city jungle-scape of San Jose.

WHO IS THE PIZOTE?

The Pizotes are mid-sized mammals also known as ‘day raccoons’ – not only because they belong to the raccoon family, but because they also share many of the raccoons’ habits (Costa Rica does have a lively raccoon population too, but raccoons are active at night so they are not as widely seen). They are between 4-6kg in weight and just over a meter long (including their long tails which can make up half of their length).

A nickname for the Pizote is ‘hog-nosed raccoon‘ – not very flattering, it refers to the animal’s pronounced and extended snout which is super flexible and can be moved 60 degrees. The snout helps the Pizote locate food hidden in the rainforest litter (or picnic-goers’ baskets)! And the animals don’t usually need to spend too much time searching as they eat *everything* – fruit & nuts, berries & nectar, small mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, fish, insects, and food scraps discarded in rubbish bins.

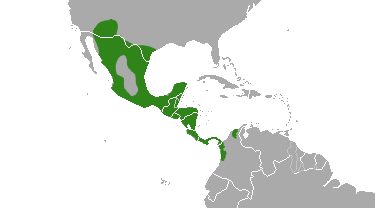

Other than the White-Nosed Coati there are three (maybe four) other species – the South American Coati (Jungles of South America), and the Eastern (Venezuelan Andes) and Western (Colombian and Ecuadorian Andes) Mountain Coatis. A disputed specie, Cozumel Island Coati, lives solely on Cozumel Island off the Yucatan Peninsula.

POLLINATORS?

Yes! It has been established that Pizotes have a dependent relationship with the Balsa tree. Costa Rican Pizotes were a subject of a study and it was observed that when the animals dip their heads into the Balsa flowers in search of the sweet nectar, their faces become covered in Balsa pollen. They then pollinate other Balsa trees as the pollen from their faces disseminates throughout the forest. So the Pizote can satisfy its hunger and quench its thirst, especially in times when environmental resources are scarce, while the Balsa benefits from a propagation boost.

FIERCE FIGHTERS!

Here is a video of a Pizote driving off a much larger Puma – PIZOTE vs PUMA – and there are stories of Pizotes successfully repelling Jaguar attacks! So it is no wonder that an encounter between a Pizote and a dog can have a very bad outcome! Pizotes have a powerful bite, can inflict very powerful scratches, and their thick skin provides a formidable defense – so it is best to keep your dogs away from these animals if possible. And needless to say, this extends to children and grownups as well – approaching and feeding Pizotes is not a good idea because the animals may become dependent on handouts and so used to people that they become a nuisance. And if Pizotes feel threatened they may attack and inflict serious injuries.

‘BANDS’ and ‘DINOSAURS’?

Pizotes thrive in social settings. They typically form bands of 3 to over 20 individuals, made up mostly of related females and their young. Males, on the other hand, tend to lead more solitary lives, joining these groups only during the breeding season.

When two bands cross paths, the encounter rarely turns hostile. Instead, the animals exchange a chorus of squeals, grunts, and chirps—an expressive greeting ritual that sometimes leads to individuals switching groups. Each band usually includes a single adult male, and as long as no rival male approaches, harmony prevails. But when another male attempts to join, tensions spike, and fierce battles often erupt as the resident male defends his place.

Because of the Pizotes’ very long tails which are often held up, a travelling band may resemble a group dinosaurs that walk backwards – see this video DINO-PIZOTE – the long tails playing the roles of extended dinosaur necks and heads. The Pizote tails are held up to help the animals keep track of each other in dense, high vegetation.

PIZOTE RANGE

The Pizote range stretches from the southern United States—possibly including introduced populations in Florida—all the way through Mexico and Central America to the northernmost reaches of Colombia. These adaptable mammals thrive from sea level up to elevations of 3,000 meters, making them one of the most widely distributed species in their range. In the U.S., particularly at the northern edge of their habitat, populations remain more vulnerable due to habitat fragmentation and limited numbers.

In Costa Rica, Pizotes are practically everywhere. You’ll spot them begging for scraps at roadside stalls, rummaging through markets, or raiding backyard banana trees. They travel in noisy, curious bands, often 10 to 30 strong, and forage through plantations with impressive coordination. Whether deep in jungle terrain or navigating the urban sprawl of San José, these animals have carved out a niche in nearly every corner of the country. Their comfort across such a wide range of altitudes and habitats speaks to their remarkable resilience and opportunistic nature.

Interestingly, there is a purported breeding population of about ten individuals in Cumbria, United Kingdom – they are animals that escaped from captivity dating as far back as 150 years ago! It is notable they are surviving in such a cold and alien climate.

HOW ARE THE PIZOTES DOING?

Outside the far northern edges of their range, Pizotes (Nasua narica) remain widespread and relatively secure. Despite frequent threats from hunting, habitat loss, and vehicle collisions, these adaptable mammals continue to survive and even flourish across much of Costa Rica. Their omnivorous diet, social flexibility, and climbing skills help them navigate changing environments with surprising resilience.

Mountain coatis, on the other hand, face more serious challenges. Species like the Nasuella olivacea, found in higher elevations of South America, contend with shrinking habitats and limited population data. The Cozumel Island coati, often debated as a separate species (Nasua nelsoni) or a subspecies of N. narica, teeters on the edge of survival. Smaller and more isolated than its mainland relatives, it suffers from habitat fragmentation and human encroachment. Conservation efforts are underway, but its future remains uncertain.

Do you dream of living in the midst of breathtaking tropical scenery and amongst amazing animals like our troublesome Pizotes? At RE/MAX WE SELL PARADISE, we list hundreds of tropical properties – homes, land, farms, estates & businesses – all within a stone’s throw of the amazing rainforests, mountains, beaches and resident exotic animals that make Costa Ballena a world-famous destination. Start your journey to paradise by browsing our property listings here.